[ad_1]

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is an increasingly common diagnosis among women in their reproductive years. Not only is it associated with adverse reproductive outcomes, but it also underlies a number of chronic metabolic conditions that affect long-term health. A recent review article in CMAJ explores the current state of knowledge regarding the diagnosis and treatment of this chronic disorder.

Background

PCOS is diagnosed if two of the following abnormalities are present:

- irregular periods

- Evidence of high androgen levels, either through clinical symptoms and signs or through blood tests.

- Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) showing polycystic changes in the ovary that fit PCOS criteria

Treatment of PCOS depends on correcting the underlying pathophysiology, whether it is the absence of ovulatory ovarian cycles, elevated androgen levels, excessive insulin levels, or weight regulation.

These patients will require long-term follow-up to determine the trajectory of their body mass index (BMI) and monitor their blood pressure, blood sugar, blood lipids, and other metabolic markers. They are also at risk for outcomes such as depression, anxiety, and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome

About 10% of women are affected by PCOS today, usually between the ages of 18 and 39. However, many patients are not diagnosed, while others are diagnosed much later.

As many as half to three-quarters of PCOS patients are likely to have excessive body weight, which is reflected in a high BMI. In turn, this affects the severity of the condition. However, PCOS is only slightly more common among women with a higher BMI, indicating that obesity plays only a small role in causing this condition.

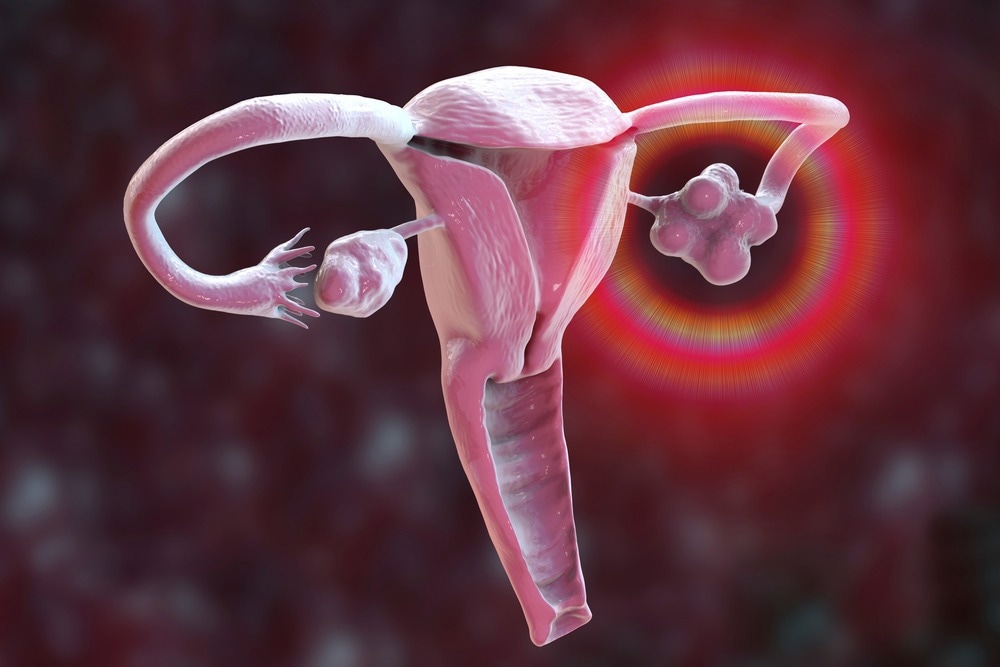

Polycystic ovary syndrome is mainly caused by excessively high levels of insulin and androgens, but the sequence of events is still unclear. The pathognomonic finding is the presence of immature follicles in the ovaries. It is possible that both hyperandrogenism and hyperinsulinemia are exacerbated by and simultaneously promote fat deposition in the body. This could be the result of a higher frequency of pulsatile release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus or functional hyperandrogenism at the adrenal or ovarian level.

GnRH stimulates the production of both follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), both of which increase estrogen levels. Estrogen, in turn, promotes the development of follicles in the ovary and reduces FSH production from the pituitary in a classic feedback loop. LH promotes androgen production within the theca granulosa cells of the ovary, and both estrogen and progesterone stimulate greater release of LH.

High androgen levels cause more follicles to begin to develop, but also stimulate their entry into atresia, producing the classic polycystic ovary phenotype in TVUS.

Too much insulin can cause LH levels to rise and at the same time make more sex hormones available to the tissues. It could also improve the conversion of weak to strong androgens in the ovary, reducing the feedback effect of LH. Finally, it promotes the deposition of fatty tissue as well as an increase in the size of fat cells.

Symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome

PCOS can cause a variety of changing menstrual symptoms, from irregular cycles to complete anovulation, while some women continue to have regular ovulatory periods. Some patients have a family history of polycystic ovary syndrome, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, or diabetes.

Androgen-related symptoms range from hirsutism and acne to thinning hair without receding. The symptom most closely associated with hyperandrogenism is hirsutism and is often the basis for initiating treatment.

The presence of purple stretch marks on the skin or fatty deposits in the region of the abdomen and back of the neck may suggest Cushing’s syndrome or a form of congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Women with heavy bleeding or breakthrough bleeding episodes usually do not have polycystic ovary syndrome, but should be examined for infections or uterine growths.

Thyroid problems or hyperprolactinemia are other similar-looking conditions that should be ruled out.

diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome

The Rotterdam criteria have been established to diagnose this condition, and other conditions are excluded by testing before reaching this diagnosis. A review of medications is mandatory as some may cause similar symptoms.

Androgen levels are only slightly elevated in polycystic ovary syndrome, while marked increases are more suggestive of androgen-secreting tumors. Women taking combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) have low androgen levels, making this test unreliable in this group.

TVUS findings of 20 or more follicles in an enlarged ovary with 1 mL or more of total volume fit a diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fewer follicles than normal may be normal, and occurs in up to a quarter of healthy women.

Management of polycystic ovary syndrome

PCOS treatment focuses on the most distressing symptoms, whether increased bleeding, acne, hirsutism, irregular periods, or excessive weight. Losing 5 to 10% of body weight can help mitigate most of these symptoms, but should be recommended without blaming or shaming the patient for her body weight. Patients with PCOS are at increased risk for body image and eating disorders.

Periods can be regularized with CHC, which also relieves hirsutism and acne by reducing androgen levels. Other options for menstrual regularity include progestin-only methods, either continuous as with implants or intrauterine devices or periodically as with cyclical or rescue use of this hormone. Continued use of progesterone causes periods to stop.

Any of these methods also guarantee the protection of the endometrium, a top priority among women with cycles longer than 90 days, since endometrial cancer rates increase between 2 and 6 times in this group.

Non-hormonal alternatives include metformin, which improves insulin sensitivity and can help regularize cycles and, as a result, reduce androgen levels, accompanied by small weight reductions. Metabolic protection is more significant among women with a BMI greater than 25, with the effects of androgens and insulin being more significant at lower BMI.

A combination of CHC and metformin may help women with a BMI over 30 and poor glucose tolerance or those at risk for diabetes. Inositol is a carbohydrate supplement from the B vitamin family. It is available without a prescription and helps reduce BMI and normalize cycles, while possibly improving insulin sensitivity.

Antiandrogens are used to treat the symptoms of hyperandrogenism, especially hirsutism, together with CHCs or as an alternative to CHCs when the latter cannot be used. Surgical laser hair removal, sometimes with the addition of topical eflornithine, is required to remove established hair that does not respond to medical treatment. Stronger antiandrogens can be harmful to the fetus and are only used if the woman uses effective contraception.

Reproductive outcomes improve with age in the PCOS population, although women may take about two years longer than average to conceive. More than half of spontaneous pregnancies reach delivery, compared to almost 75% among spontaneous conceptions without polycystic ovary syndrome. Among women receiving assisted reproductive technology (ART), success rates are the same as women without PCOS, at 80%.

Conservative treatments such as weight loss and metformin, inositol or the GnRH inhibitor letrozole can be tried initially in women under 35 years of age, followed by more aggressive treatment. The latter includes laparoscopic ovarian drilling or fertility treatment.

During pregnancy, women with PCOS should be monitored for miscarriage, excessive weight gain, diabetes, hypertension during pregnancy, and fetal growth problems. Premature birth and cesarean delivery are also more likely.

To mitigate the long-term risk of health complications associated with PCOS, especially with a BMI greater than 25, annual and baseline health assessments are recommended. OSA is ten times more common with PCOS, while the risk of depression and anxiety more than doubles.

Conclusion

In view of the high prevalence, severe symptoms, and significant long-term consequences of PCOS, greater attention should be paid to early diagnosis and appropriate treatment of this disorder.