[ad_1]

ANALYSIS OF ARGUMENTS

By Amy Howe

February 8, 2024

at 15:14

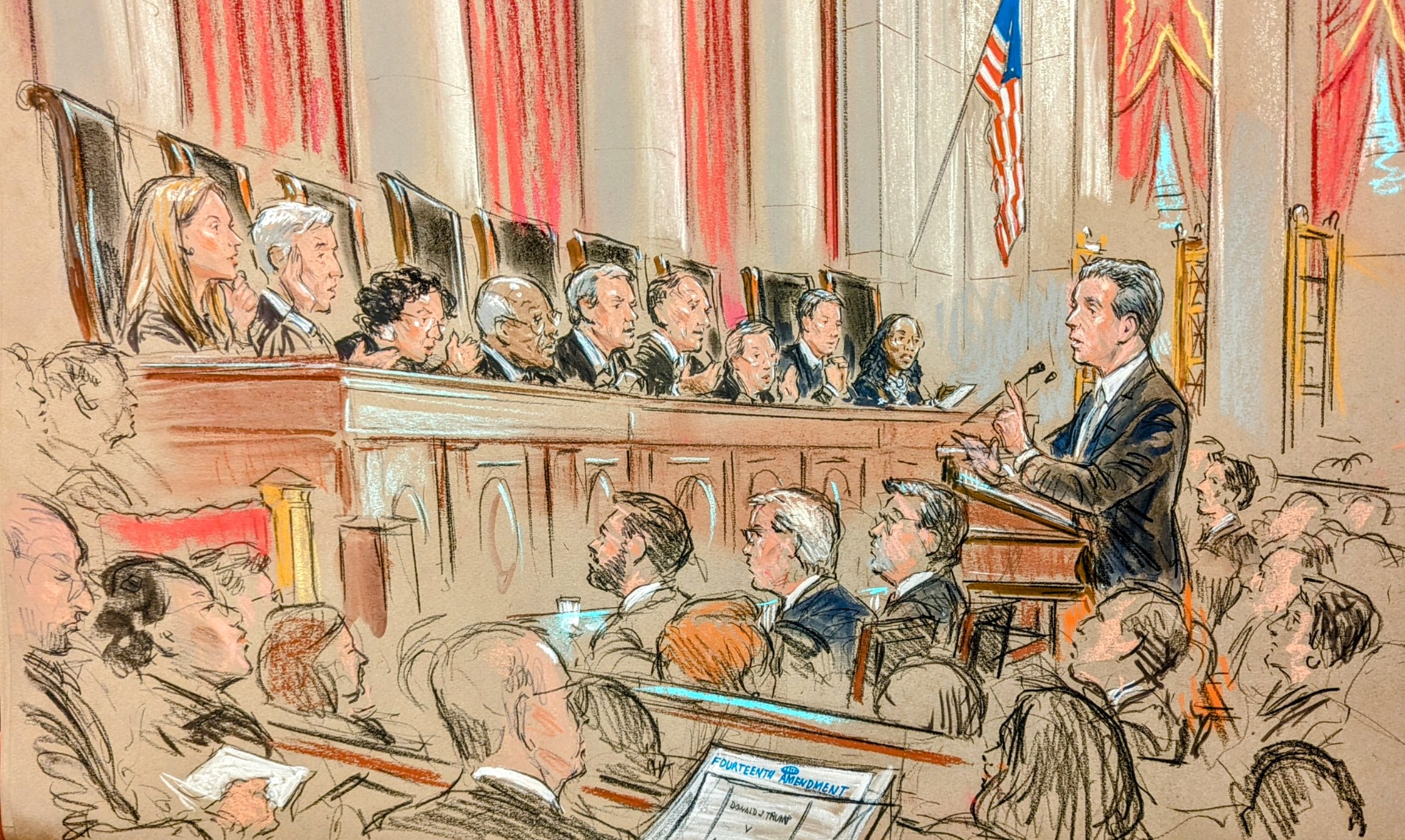

Jonathan Mitchell defends former President Donald Trump. (William Hennessy)

The Supreme Court on Thursday appeared set to hold that Colorado cannot exclude former President Donald Trump from the ballot for his role in the Jan. 6, 2021, attacks on the U.S. Capitol. During an oral argument that lasted more than two hours, justices of all ideological stripes questioned the wisdom of allowing a state to make its own decisions about whether a candidate should appear on the ballot, both because of the effect such decisions would have on the rest of the country and by the obstacles that the courts would face when reviewing those decisions.

The case centers on Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, which was enacted in the wake of the Civil War to disqualify from holding public office people who had previously served in the federal or state government before the war but who later supported the Confederacy. It states (as is relevant here) that no one “shall be a senator or representative in Congress, or an elector of president and vice president, nor hold any office, civil or military, under the United States or under any state,” if that person had sworn previously, “as a member of Congress or as an officer of the United States,” supported the Constitution, but then “engaged in an insurrection or rebellion” against the federal government.

Last fall, a group of Colorado voters went to court, seeking to have Trump disqualified from appearing on the ballot under Section 3. A lower court agreed that Trump had participated in an insurrection, but still refused to remove it from the ballot because it concluded that the presidency is not an “office…under the United States” and the president is not an “officer of the United States.” USA”.

The Colorado Supreme Court ruled on Dec. 19 that Trump is ineligible to be president under Section 3 and should not be on the primary ballot. The court stayed its ruling to give the Supreme Court time to weigh in, which the justices agreed to do on Jan. 5.

Representing the former president, attorney Jonathan Mitchell told the justices that states cannot use Section 3 to prevent Trump from running for office – that is, remove him from the ballot – because Section 3 also leaves open the possibility that Congress can, by a two-thirds majority vote, lift the ban that Section 3 would impose after Trump is elected but before he actually takes office.

And, in fact, Mitchell said in response to questioning by Chief Justice John Roberts, under that reasoning a state could not exclude a candidate from the ballot even if he or she publicly admitted to being an insurrectionist.

Mitchell compared the events before the court to an effort by one state to require congressional candidates to live in the state before Election Day, when they are only required to live there when they are elected. In both scenarios, Mitchell argued, states are “accelerating the deadline for meeting a constitutionally imposed qualification.” He warned that upholding the Colorado Supreme Court’s decision would “take away the votes of potentially tens of millions” of voters.

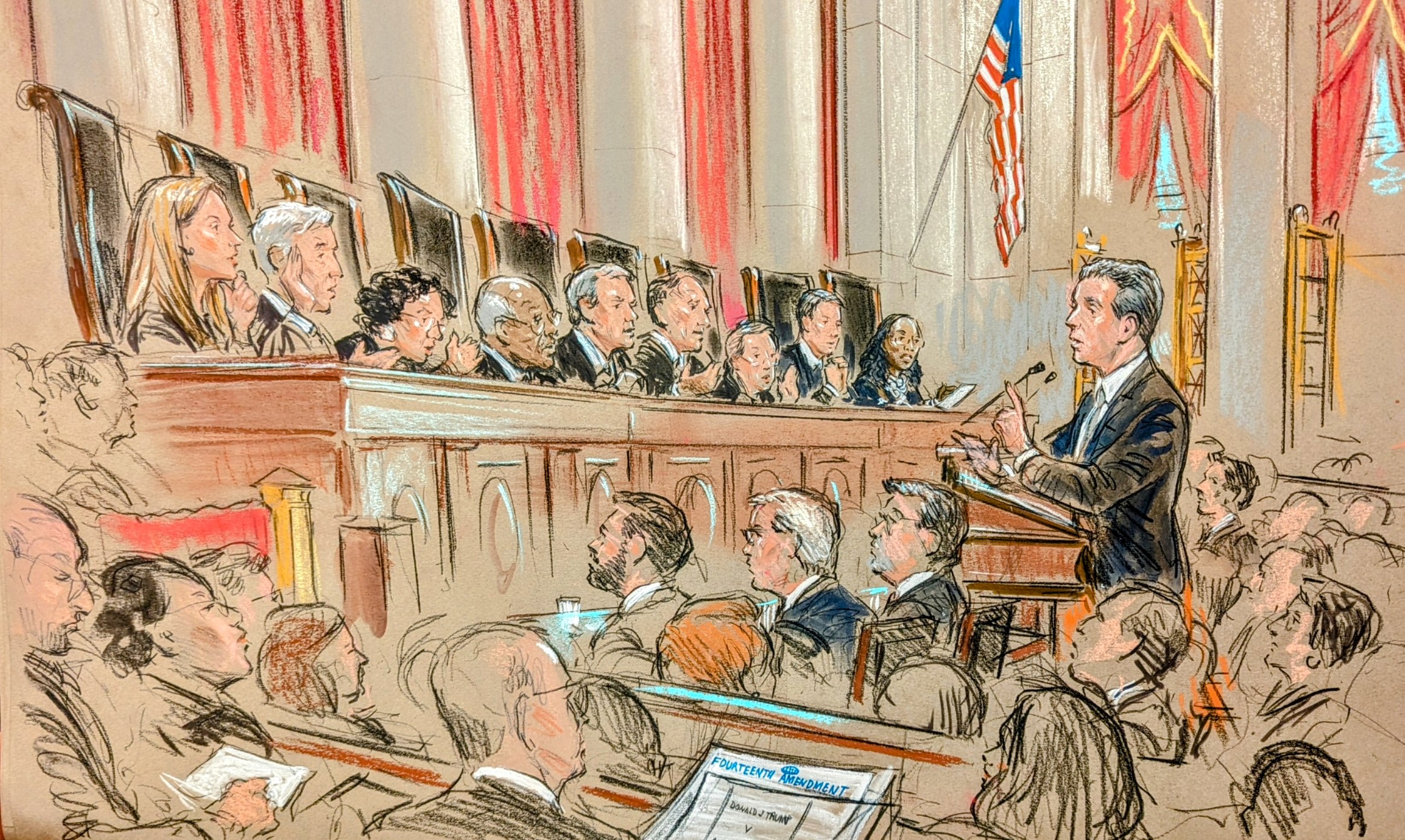

Jason Murray stands up for Colorado voters. (William Hennessy)

Jason Murray, representing voters challenging Trump’s placement on the Colorado ballot, began his argument by painting a dire picture of the events of Jan. 6, telling the justices that “our nation’s capital was targeted.” a violent assault” for the first time since the war. of 1812. “For the first time in history,” Murray continued, “the attack was incited by a sitting president of the United States to disrupt the peaceful transfer of presidential power.” “By engaging in an insurrection against the Constitution,” Murray said, Trump “disqualified himself from holding public office” and now argues that the Supreme Court should create a special exception that, as a former president who did not hold office before getting elected, the White House – would apply only to him.

A central issue in Thursday’s argument was whether the question of how Section 3’s ban on government service by people who have “participated in the insurrection” can be enforced: Do states like Colorado have the power to do so? enforce it themselves, as voters maintain, or (as Trump maintains), can it only be enforced through laws passed by Congress?

Some justices turned to history and pressed Murray to provide examples of other scenarios in which states have relied on Section 3 to disqualify candidates for federal office. Murray pointed to a congressional election in Georgia in 1868, as well as state elections and candidates disqualified by Congress, noting that the paucity of examples was “not surprising” because elections worked differently then, with voting for political parties in instead of individual candidates. . Therefore, he reasoned, “there would have been no process to determine before an election whether a candidate was qualified.”

But that response did not appease Justice Clarence Thomas, who observed that the “plethora of Confederates” still present in public life in the post-Civil War era would suggest that this issue would arise.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh echoed Thomas’s emphasis on the absence of historical examples as evidence that states do not have the independent power to disqualify candidates under Section 3. He cited The Griffin case, an 1869 decision by Chief Justice Salmon Chase, in a lower court. In that case, Chase ruled, Section 3 can only be enforced by laws passed by Congress.

Although the decision is not binding on the Supreme Court, Kavanaugh suggested that a year later Congress had The Griffin case in mind when he enacted the Execution Act of 1870, which gave the Justice Department the power to file lawsuits seeking to disqualify federal officials. For 155 years, Kavanaugh concluded, no state has attempted to disqualify a federal official from the ballot under Section 3 because “there has been an established understanding” that states do not have that power. Furthermore, he added, “Congress can change that,” but it hasn’t.

Murray responded, suggesting that no state had attempted to disqualify candidates for federal office because there had been no need to do so. Virtually all former Confederates had received amnesty in 1876, so it would no longer be necessary to disqualify them from the elections, he observed. And since then, he maintained, there was no reason to invoke Section 3 because the country had never experienced anything like the January 6 attacks.

Justice Samuel Alito was unmoved by this line of argument. He noted that there were no presidential impeachments between 1868 – when President Andrew Johnson was impeached – and President Bill Clinton’s impeachment trial in 1998. But since 1998, he stressed, there have been three: Clinton and Trump’s two impeachments in 2019 and 2021. .

But on the question of enforcement, the court focused even more specifically on the potential implications of upholding the Colorado Supreme Court’s decision. Justice Elena Kagan was one of those who most expressed her concerns. Why, she asked, should a state be able to disqualify a candidate from the ballot and, in doing so, effectively determine who becomes president of the United States? Rather than seeming like a question for an individual state to decide, she said, that “sounds terribly national to me.”

Judge Amy Coney Barrett seemed to agree. If the court upholds Colorado’s ruling, she said, it will effectively decide the issue for all other states. Like some of her colleagues, she imagined possible logistical problems and noted that the court would have to make its decision using the facts developed in whichever state court case came to them first. In a scenario where the factual record is not well developed, she asked, how should the court review those findings? “It just doesn’t seem like a state decision,” she concluded.

Alito weighed in, noting that other logistical problems could arise if states reach different conclusions on issues arising from Section 3, such as whether a candidate “engaged in an insurrection.” In that case, Alito asked, how should the Supreme Court proceed? Would he have to decide the rules of evidence, determine who would bear the burden of proving the candidate was an insurrectionist, or even hold his own trial?

But even more broadly, both Alito and Roberts were wary of what Alito characterized as the potentially “cascading” effect of upholding the Colorado decision. If the Supreme Court were to rule that Trump can be removed from the Colorado ballot, Roberts said, it would undoubtedly lead to efforts to disqualify the Democratic presidential candidate. “And some of them will succeed,” leading to a scenario in which only a “handful of states… are going to decide the presidential election.” “That’s a pretty discouraging consequence,” Roberts concluded.

Colorado Attorney General Shannon Stevenson defends Colorado Secretary of State. (William Hennessy)

Colorado Attorney General Shannon Stevenson, defending Colorado Secretary of State Jena Griswold, attempted to allay some of the justices’ fears. She told the court that disparities between ballots in different states are a feature, rather than a bug, of the democratic process, and urged justices to allow the process to play out even if it becomes complicated. “Congress,” she emphasized, “can act at any time if it believes” the process has truly “gone crazy.”

And Stevenson downplayed the possibility of retaliation against Democratic candidates if the court were to uphold the state court’s decision, arguing that “we have to have faith in our system” and the “institutions in place to handle those types of allegations.”

But after more than two hours of discussion, the justices seemed unwilling to agree with Stevenson and leave the Colorado Supreme Court’s decision in place.

There is no way to know when the judges will issue their decision. The Colorado Supreme Court ruling is currently on hold, so Trump will remain on the ballot there unless the justices rule otherwise, but the court is likely to move relatively quickly to resolve the matter because of its importance to other states where there are challenges to your eligibility. are pending.

This article was originally published on Howe on the Court.

[ad_2]

Source link