[ad_1]

Although it is the predominant theory now, the road to acceptance was long and bumpy for tectonic plateswhich describes how large portions of the Earth’s crust slide, grind, rise and sink very slowly across its muddy surface. mantle.

But even now, more than half a century After being given scientific approval, the theory needs some refinement.

A new study analyzing four plateaus in the western Pacific Ocean suggests that these expansive areas are not rigid slabs but rather weak points where distant forces are tearing away at the plate edge.

“The theory is not set in stone and we are still finding new things.” says Russell Pysklywec, a geophysicist at the University of Toronto, co-author of the study.

“We knew that geologic deformations, like faulting, occur inside continental plates, far from plate boundaries. But we didn’t know the same thing was happening with oceanic plates.” add First author Erkan Gün, also an earth scientist at the University of Toronto.

For decades, scientists have been rewriting their understanding of the seafloor, so this new study is just a continuation of their efforts to map the ocean’s rugged topography.

In the 1950s, ocean cartographer Marie Tharp’s pioneering work to map large parts of the seafloor Using sonar data from warships showed that the ocean basins were not at all flat surfaces as scientists had suspected.

Rather, the seafloor was divided by enormous trenches and enormous mountains, none larger than the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, which Tharp discovered and is now recognized as the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. longest mountain range on the planetdividing the Atlantic Ocean in two.

Similar mountain chains are formed when two tectonic plates collide and the Earth’s crust warps, or one plate sinks beneath the other, pushing the upper plate upward. However, underwater, seamounts usually form when two plates separate at the so-called divergent boundary and magma shoots out.

But far from these plate boundaries, in the centers of the oceanic plates, scientists thought that large sections of the Earth’s crust remained fairly rigid while floating on the mantle, and did not deform like the edges of the plates.

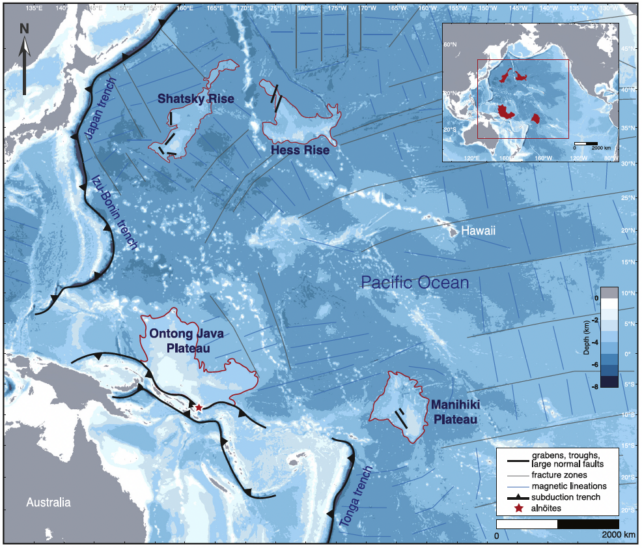

To test this thinking, Gün, Pysklywec and their colleagues collected existing data on two oceanic plateaus lying between Japan and Hawaii called Shatsky Rise and Hess Rise; the Ontong Java Plateau, north of the Solomon Islands; and the Manihiki Plateau, northeast of Fiji and Tonga.

Given the challenges of studying the seafloor, their study was limited to these four plateaus in the western Pacific Ocean for which data were available.

Oceanic plateaus are located hundreds or thousands of kilometers from the nearest plate boundary. However, Gün and his colleagues found that the plateaus shared deformational and magmatic features that suggest they are being torn apart by attractive forces at the edge of the Pacific plate, where the slabs are being subducted beneath neighboring plates.

The ruptures, or fault lines, identified by the researchers tend to run parallel to the nearest trench, as can be seen in the map above.

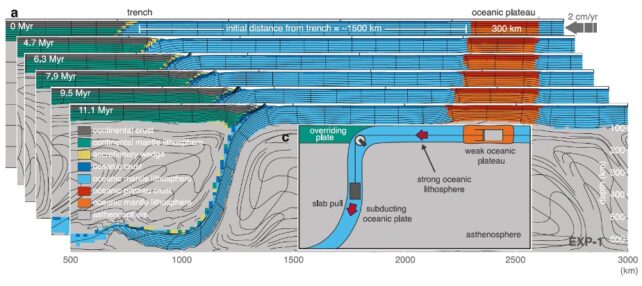

The team also modeled the plate tectonic dynamics of four hypothetical plateaus located between 750 and 1,500 kilometers (466 to 932 miles) from the nearest subduction zone, to better understand the mechanisms that give rise to this distant deformation.

Regardless of their distance from the plate edge, these hypothetical plateaus stretched over millions of years and became thinner on the side closest to the trench.

“It was thought that since the suboceanic plateaus are thicker, they should be stronger,” says Gün. says. “But our models and seismic data show that it’s actually the opposite: the plateaus are weaker.”

Acknowledging that they only analyzed four Pacific plateaus, the researchers hope their findings will prompt further exploration to map the seafloor.

“Sending research vessels to collect data is a big effort,” Gün says. “So we’re actually hopeful that our paper will draw attention to the plateaus and more data will be collected.”

The study has been published in Geophysical research letters.