[ad_1]

The history of Chinguetti Meteorite It is a very compelling mystery.

The 4.5-kilogram (10-pound) iron rock was reportedly mined from the top of a giant 100-meter-wide (328-foot) iron mountain (believed to be a huge meteorite) in Africa there. by 1916.

Despite numerous searches, the existence of this larger meteorite has never been confirmed. Now, a team of researchers is back on track.

If it existed, this mountain of iron would represent by far the largest meteorite on the planet, and scientists at Imperial College London and the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom want to use maps of magnetic anomalies (like large blocks of iron) to try. . to find it.

For starters, the smallest piece of meteorite was originally recovered by Captain Gaston Ripert, a French consular official, who said that a local chief had blindfolded him and guided him up the “iron hill.”

The meteorite is named after the nearby town of Chinguetti, in Mauritania, northwest Africa. All subsequent attempts to find the gigantic iron mountain of which it was originally a part, until the 1990s, have failed to find the location to which Ripert was taken.

And what is more, a 2001 study concluded that the stone-iron fragment mesosiderite It could not come from a mass with a volume greater than 1.6 meters in diameter, according to a chemical analysis of the metal.

Was Captain Ripert lying? Or just wrong?

Perhaps neither of the two things, say the latest researchers who have undertaken the mission to find the Chinguetti meteorite. The lack of an impact crater could be due, for example, to the meteorite entering at a very low angle before hitting the ground.

Previous searches may have turned up nothing because the iron mountain had been covered in sand, or because the instruments used were not accurate, or because the search area was in the wrong place according to Ripert’s vague instructions. These are all possibilities, scientists say in a new paper.

Perhaps most interesting is that Ripert specifically described one feature of Iron Hill. The captain described finding extracted metal “needles” that he unsuccessfully attempted to knock away from his smaller meteorite sample.

The authors of the paper speculate that these ductile structures could be nickel-iron phases known as “Thomson structures.” Unheard of in 1916, it is unlikely that Ripert would have invented such an observation.

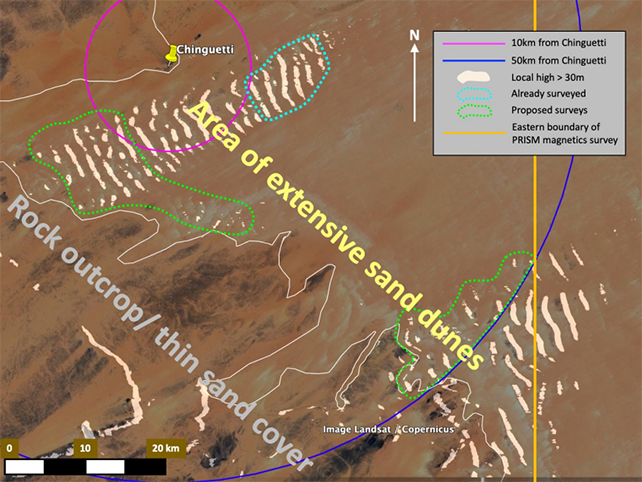

For the first time, investigators used digital elevation models, radar data and interviews with local camel riders to narrow down areas where Ripert could have been taken, based on his report of a half-day trip.

Using the heights of dunes that could be hiding the giant meteorite as a guide, the team identified areas of interest and requested aeromagnetic survey data for these locations from the Mauritanian Ministry of Energy and Petroleum Mines. So far, access to that data has not yet been given.

An alternative approach would be to explore the region on foot in search of the long-lost meteorite, although this could take several weeks.

“However, if the result is negative, Ripert’s explanation of the story would remain unresolved, and the problems of ductile needles and the coincidental discovery of mesosiderite would still exist,” write the researchers.

The researchers’ new findings have not yet been peer-reviewed, but can be accessed on the preprint server. ArXiv.